The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen, nor touched, but are felt in the heart.

~Helen Keller

It was a normal work shift for me, evening weekends in Labor/Delivery. The usual hustle and bustle of work-week procedures was not there, so it normally wasn't as busy. Sometimes a full moon or a bad storm would bring in more business, but usually the pace was not too busy.

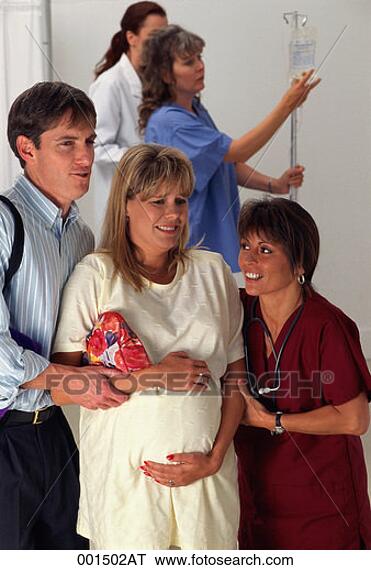

On this particular Sunday evening, one of our obstetricians called the unit to tell us he was sending in a patient who thought she was in labor. It was her first baby. I was asked by the charge nurse to admit this patient and take care of her. I got out the prenatal file we had for her, and reviewed it. It read like a textbook healthy pregnancy. She was a teacher, married to another teacher. This was going to be a fun evening!

The patient and her husband arrived, looking a little anxious but excited. She went into the bathroom to put on a hospital gown, so I chitchatted with her husband and got the fetal monitor ready. She bounced out, a little flushed with excitement. I remember thinking they looked like Barbie and Ken, here to have their first baby.

I applied the fetal monitor and oddly, didn't hear anything. I readjusted it several times, but heard nothing. Not just nothing... there is a gut wrenching kind of silence an experienced OB nurse fears. That was what I was getting. Absolutely nothing-- void of any sign of life. Smiling and trying to speak calmly, I asked the patient when she had felt the baby move last. "Oh last night!" she said. "The baby was very active last night. It was breech for awhile, and I think it might have turned last night." My heart sunk. Plummeted to my toes. "Well, I am having trouble finding the baby's heartbeat, so I am going to go find another nurse and see if she has any better luck." I said.

Shaking, I went to the desk and told the charge nurse my findings. "Will you come and see if you hear anything?" I asked, and of course she did. Both of us adjusted and readjusted that monitor a thousand times. This was before the days of portable ultrasound machines, so we would have to send her downstairs to the big ultrasound machine in Nuclear Med. And the physician needed to know. "I am going to go call your doctor, to let him know we're having trouble," I said. I tried to look her in the face, and when I did I could see the mounting panic. Her husband was silent. Much paler than when they walked in the door and no longer smiling. Tears were welling in both their eyes. "Oh dear God..." I prayed. "Help me help these darling parents... " I went out to the desk and called the physician. I know these phone calls are the absolute hardest ones for a doctor to get from L&D. He gave an order for the ultrasound test and said he'd be right over.

I accompanied the patient to Ultrasound. This was in the days when husbands were not routinely allowed in that department, but I told the tech I was bringing him down to support his wife. The findings from the test revealed the baby's heart was not beating. The baby would be stillborn. The parents could not see the screen, and the tech was not allowed to give them this information. I knew the physician would not want me to give it to them either, but I also knew they weren't stupid. I could not lie to them. Helping them wait for the truth was going to be hard.

We went back upstairs with me telling them we'd have to wait to hear from the radiologist who would read the test images and from the physician. I told them I wasn't an ultrasound tech, so I wasn't qualified to read the images myself. I told them not hearing the heartbeat was a bad sign. The patient began to cry softly. She and her husband held hands while she wept. Her husband looked devastated, but did not cry.

It seemed like hours, but was really probably only 15 or 20 minutes before the physician knocked and entered the room. He gave the devastating news to the couple as gently as he could. He said he suspected there had been some kind of "cord accident" when the baby had turned the night before. He told them how sorry he was, but that he needed to take care of the mother now and that he wanted to induce labor so the pregnancy would end quickly. The stunned parents nodded their agreement to his plan. The physician left the room. The patient began to sob openly, and reached for her husband who held her tight. She sobbed and sobbed. There was nothing more I could do at this point, so I tiptoed out of the room. I needed a break myself... remaining professional so I could care for her during what would probably be a long labor was important.

A hush had come over the unit, as it always does with situations like this. I sat for a moment to compose myself. Several staff nurses patted me on the back and asked if they could help me. The physician was still on the unit, and he looked solemn. "I am going to wait this out back in the call room," he said. "Call me if you need anything." I got up and gathered the equipment necessary to begin the induction and reentered the room.

It didn't take as long to deliver the baby as I had feared. Sometimes nature kicks in and helps out in these situations, and she delivered before the end of my shift. She labored bravely, and was supported by her husband. I remember she told me that coping with the labor gave her something to focus on, and while she knew the outcome, she still was trying to remain hopeful. Her husband did not shed a tear during the entire labor. He rubbed her back, stroked her hand. He whispered words of support and love in her ear. He helped her push when it was time.

The baby was delivered by the physician, and was a beautiful baby girl. Perfect features, round and fat like the Gerber baby. At delivery the physician noted a large knot in the umbilical cord. Cursing quietly under his breath, he showed the parents. "I'm so sorry..." he said, and his eyes welled up. Then he cursed again, and left the room.

In the long-ago bad days, a stillborn baby would have been whisked out of the room as if it had never existed. The parents would have been shipped off to another unit away from OB. They would have been encouraged to forget all about this baby, and look immediately to the future to have another. In our efforts to cushion the grief, I fear we did terrible wrong to parents who experienced this kind of loss. No more... medical professionals had learned how wrong an approach that was. I wrapped the baby up in a blanket and gave her to first the mother, then the father. They looked at all her features, and through tears admired them. They stroked her hair. They each hugged her close. They named her Sarah. I remember the father holding his baby, talking softly to her. "Oh Sarah... little girl..." he said. "If only you had made it. We have so much stuff waiting on you at home... You have grandparents who are waiting for you... and friends... and so much love to share with you..." And then he started to cry. Great wracking sobs came from this gentle man. Heart broken, he cried as he carried the baby back to his wife for her to hold. They held one another and cried. And cried and cried.

That was when I had to leave. My shift was over. I had my own family waiting on me at home, and still had a mountain of paperwork to complete. Despite my need and theirs for me to continue their care, I told them I had to go and that eventually a night shift nurse would come in to see how they were doing. I don't remember, but I probably even brought her in and introduced her. That nurse would have to complete the business side of this event-- funeral home arrangements, etc. That seems to me to be the worst part of grief-- that there is a business side at all to cope with.

It has probably been 25 years since this happened, and I still think about these people. I hope they were able to have more children and that they could continue to support one another in their grief as well as they did that day. It was a very difficult assignment for me as a nurse, but it wasn't the last time I had to care for people who would not go home with a live baby. Every one of those situations touched my heart, and opened it to the world of hurt and grief that exists. Every time someone learns I worked in Maternity, they respond with "Oh that is such a happy place!" And that always reminds me of this family. And all the others... "Not always..." has been my usual response.

Nursing opened my heart to the pain of others unlike nothing else. Images of starving children or natural disaster victims on TV can get to me sometimes, but working one-on-one with people who are hurting, either physically or emotionally forced me to open up and respond in a personal way to each situation. Nursing has made me a better human being. And I hope that what I gave back to these people in some way measured up to what they gave to me.